The Irishman in The Himalayas: A Story from Sujanpur, Himachal Pradesh

| Inside the Baradari Hall at Sujanpur Tira |

When a Hamirpuri finds a book on Pahadi art, authored by a Punjabi Civil Servant, stashed in the dusty racks of a Chandigarh museum, and reads about the musings of a Kangra king who was served by an Irishman—where does that imagery take you?

Unity in diversity, that old maxim, does it ring a bell? Oh, spell it out, spell it out:

We take you straight to India. Ixnay, not Rushdie’s India, the Real India.

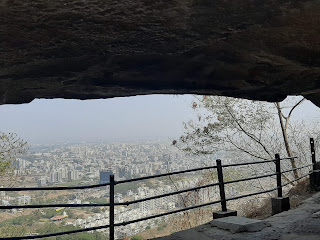

In the sleepy old town of Sujanpur, perched atop an escarpment, lies the grave of an Irishman, who, perhaps, loved the Beas a little too much to be buried next to it. The man’s dying wish granted—to look at it, endlessly meandering through the valley, touching the toes of the half-inch Hamirpur Himalayas.

| The 'half-inch Himalayas' from the vantage point of Col O'Brien |

This little hamlet in the hills, with its narrow alleys, is a graveyard of Pahadi history, where ‘today has built its mud walls from the dust of yesterdays.’ A cool puff from the snows of the Dhauladhara reminds one of the Raja’s other capital–Nadaun: the narrow lanes of the bazaar and the tidal onslaught of vendors.

Set along the lower southern slopes are cramped houses, which prod their faces into other unwilling houses. Their lattice windows stare bleakly at the odd passer-by, gleaming through arches that slant askew on time-tested brickwork and staggered crumbling heaps of plaster and people.

| Inside the Baradari Hall at Sujanpur Tira |

| The broken roof of the Baradari Hall at Sujanpur Tira |

| An immortal(and idiotic) declaration of love at Sujanpur Tira |

Bypassing this travesty, on a winding trail at the right bank of the Beas, lies the grave of the protagonist of the story.

The Irishman, who goes by the name of Colonel William O’Brien, climbed on the stepping stones of history in the 18th Century. How did he come here? Who was he? His was a brief debut, in an obscure theatre on the outpost of the Himalayas. It was oft visited by the occasional traveller—a Travech here, a Moorcraft there.

The theatre, though, has now tumbled; the little left is the traveller’s tale.

~

“From Nadaun, we crossed the mountains to Shujanpur(Sujanpur), nine kos.

A violent thunder-storm and hurricane on our march ushered in the rains. After it had ceased, and we had resumed our progress, I was met by a Mr. O’Brien, an Irishman, in the service of the Raja, who conducted me to a bangalo, where I found refreshments prepared for me.

O’Brien, who is a strong, stout man about forty, was a dragoon in the 8th, or Royal Irish. It is said that having come on guard without some of his accoutrements, he was reprimanded by the officer, and on his replying insolently the latter touched or struck him with his cane.

O’Brien knocked him down with the butt end of his carbine, and then set spurs to his horse and galloped off. Not daring to return to his regiment, he wandered about the country for some time, and at last found service with Sansar Chand, for whom he has established a manufactory of small-arms and has disciplined an infantry corps of 1400 men,” writes Moorcraft, the traveller, who curiously became the king’s sworn brother by drawing blood off of the king’s real brother. Yet, we (mis)lead you on, for this is a tale reserved for another time.

It is not certain whether O’Brien belonged to the 8th or 24th Light Dragoons, but by this time the British had gained a significant stronghold in much of the country. The only places in the north out of their control were parts of Punjab and the Western Himalayas. One can imagine the Firangi running away from certain death to such a place.

The exact time of his arrival at the court of Sansar Chand is not known, but by 1814, he had raised a considerable body of soldiers. If not for the Anglo-Nepalese War, perhaps, this would be the extent of our knowledge about the Irishman—but the need for auxiliary troops, adopted to the mountainous terrain, prodded the British to seek Sansar Chand’s aid, whose troops were well suited for the job.

There are also mentions of O’Brien in the Punjab records. One entry from 1815 reads:

“28th November 1815––From Mr Metcalfe, resident at Delhi, to the Government of India. I lately noticed that a European had been received and entertained at Sansar Chand’s court, whom I suspect to be one of the deserters from Karnal. We cannot call upon Ranjit Singh to deliver up these deserters, who may have taken service with him, for he could not consistently comply with honour. To do so would be discreditable to the weakest state in India. I rather think the men are with that man in Sansar Chand’s service, who calls himself Colonel O’Brien, and who is a deserter from the 24th Light Dragoons, for he has made several attempts to induce Europeans to desert, and is probably the cause of the late desertions.”

Some letters addressed to a Mr. Heaney have been attributed to Col. O’Brien. Matthew Heaney was the name under which O’Brien enlisted for the army, perhaps, because at the time the army was considered the meanest of professions, and quite a number of soldiers dropped their actual name.

“Mr. Heaney,––

I received your letter. If you bring 1,000 good hill-men into my camp one month from this date, I will ensure you from Government Rs. 250 per month for life,” writes Ochterlonet, with the object to take O’Brien and his troops under British service, for Sansar Chand had evaded his voluntary promise to co-operate against the Gurkhas. “ The Raja of the Bilaspur’s country, on this side of the Sutlej, is under the protection of the British,” he writes. “ If your Raja had not been a fool and a liar, it might have been his before he(Bilaspur) accepted British protection. Whatever Bilaspur may be, he cannot be worse than your own master.”

“I have received your letter,” wrote Heaney, in response. “ I have also told the Raja I am leaving his service. All I am waiting for is to get some troops settled that I have under my command. I have eight or nine horses that I mean to dispose of, for I cannot keep them on Rs. 250 per month, as also I have some other property I mean to dispose of. I can join you in 20 to 25 days, as these mountaineers are very false people and great liars. I will let you know the wages of the whole of them when I meet you, which will be as quick as possible the accounts are settled. “

He never left Sansar Chand’s service. He died in 1827 with a total estate worth Rs. 60,000, all of which was later taken over by the son of Raja Sansar Chand.

A cloth merchant of Ludhiana had raised a claim against the estate of O’Brien, for a sum of Rs. 600. The Raja’s son declined to pay back the debt.

And so, ended the tale of the lone Irishman among ‘mountaineers’.

~

We end our little sojourn in the small hamlet of Sujanpur, and night falls as we leave the town, drawing a gossamer veil of grey across the rills.

The first breeze of the night-wind brings the scent of decaying pine needles from the valley below, as a looming moon prepares to turn the verdant valley to a lifeless silver.

It is, now, that we must bid the town farewell.

We turn around, one last time, and to ol’ Matthew Heaney, we say:

“But since it falls unto my lot

That I should rise and you should not

I gently rise and softly call

Good night and joy be with you all”

| Divyansh Thakur is a Research Wing Member at Speaking Archaeologically since October 2017 |

| Here lies Colonel William O'Brien |

| Secular Kangra Art on the walls of the Mausoleum |

| The Mausoleum has been left in care of the elements |

| Inside the Narbadeshwar temple Addendum: All photographs courtesy of Prashant Gautam |

The blog is sooo beautifully written 🌻

ReplyDeleteLoved the blog!! ✨

ReplyDelete❤️

ReplyDeleteSir zeheri blog

ReplyDeleteSo wonderfully written!! Really felt like I was reading Dalrymple 2.0 (since you have only read one book by Dalrymple, the 2.0 tag is a perfect fit here)!!

ReplyDeleteDiptarka, you should be in the Amitava Ghosh camp.

DeleteWonderful write up. Full of creativity and a sense of freshness.

ReplyDeleteWonderful write up. Full of creativity and a sense of freshness.

ReplyDeleteIt was an absolute delight to read the blog! I could almost imagine myself on the site. The tale of Irishman was mesmerizing and I almost never wanted this blog to end. A very great job done!

ReplyDeleteThank you, Simran. Glad you liked it.

DeleteThis is more a novella than a blog i was almost transported to the scene...this is a talented man. lovely work!

ReplyDelete"This was exactly the information I was looking for. Thank you for providing such clarity!"

ReplyDeletegondola shelving