“Once through this

ruined city did I pass

I espied a lonely

bird on a bough and asked

‘What knowest thou of

this wilderness?’

It replied: ‘I can

sum it up in two words:

‘Alas, Alas!’”

-Khushwant Singh

|

| Members Diptarka, Simran and Debyani at the site. |

I still remember those trips to my grandparents’ house in

Faridabad. Almost with a childlike wonder, would I ask them, whenever we passed

by Tughlaqabad, “What is that ancient looking, broken structure? Does anyone

live there?” and their response would usually include a laugh and the retelling

of the famous story of the curse of Tughlaqabad. That curiosity, though

diminished over the years, still left that little spark in the corner of my

mind. And so when Diptarka suggested we take up Tughlaqabad for our site cover

assignment, I instantly said yes, for that spark rekindled again. And so we met

at the Tughlaqabad metro station, with a big INTACH board about the Tughlaqabad

fort greeting us, nudging us forward on our journey to the fort.

|

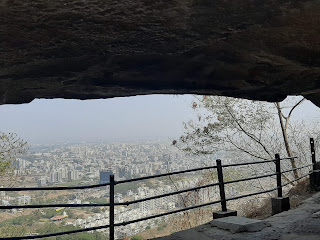

| Fig 1: A view of the long corridor with ruins of the room. |

Located on the Mehrauli- Badarpur road, the site today is

surrounded by a bustling, modern settlement of contemporary Tughlaqabad with

industries nearby. The “concrete jungle” exists almost simultaneously along

with the ruined fort structure.

The site in question was built over a period of four years,

starting from 1321 CE, by the first ruler of the Tughluq Dynasty, Ghiyath

al-Din Tughluq. The town of Tughlaqabad was not just a new capital city to be

established but also served as a symbol for a new dynastic power coming into

place, a message clearly put across through its sprawling, massive structure. A

story regarding the origin of this site goes like this: One day when Ghiyath

al-Din was on a walk with Qutb al-Din Mubarak Shah, he recommended the Sultan to

built a city on this site. The Sultan in response told Ghiyath al-Din to build

it when he would become the king. And as fate would have it, Ghiyath al-Din

became the Sultan and established the city of Tughlaqabad. Another reason might

have been protection from the Mongol invasions.

We arrived at the site and were greeted with the ASI sign

declaring the fort as a protected monument. This sign, which we would later

discover to our dismay, felt like an illusion that covered the ruinous state

inside. One could see the Tomb of Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq, now cut off from the

fort complex by the busy road standing between the two. We decided to explore

the Tughlaqabad fort first and then the tomb.

Starting with the Southern portion of the fort, we came

across a long corridor alongside the fortification wall which may have housed

various rooms, although it was now in ruins. A beautiful yet sad scenery was

painted before us and as we ventured in, we came across some really striking

parts of the palace, covered with a very thick vegetation cover, as if

wilderness had engulfed this once magnificent place completely. Debyani even

remarked that some of the ruins looked like those from Rome. However, there

were no proper paths leading to the different structures and various insects

and reptiles roamed around the whole area, thus making it almost impossible for

us to explore the various parts of the fort alone.

|

| Fig 2: Ruins of an arched structure in the Southern portion of the fort. |

In order to bring in some lived experiences into our site

cover, we decided to interview one of the caretakers at the fort, who had spent

some 50 odd years of his life cleaning and looking after the fort complex,

subsisting on the meager salary that the government provided him in exchange.

We also met a really helpful guard working there, who gladly came to our rescue

and offered to show us areas where we, otherwise, wouldn’t have been allowed to

go to. This was accompanied by a rather informative, interesting explanation of

each structure by the guard. For instance, we were told that one of the rooms

in the long corridor in the southern portion

was probably one of the earliest examples of a maze. Or how the baoli in

the same area was one of the major sources for water supply in the city of

Tughlaqabad.

|

| Fig 3: A baoli in the Southern part of the fort. |

One thing that really came as a surprise to us three was the

fact that with all the people that we interacted with, none of them believed

the story of the curse or some other myth related to the site (cue in the Curse

of Nizammudin). Rather the guard told us that the real reason for the

abandonment of this city might have been a water crisis as Delhi was prone to

water shortages. He also blamed Muhammad

Bin Tughluq’s abandonment of the city too. It is true that famines had become a

huge problem during that time and Muhammad Bin Tughluq had moved onto Adilabad

just after Ghiyath al-Din’s death.

|

| Fig 4: Members carrying out an interview with the caretaker. |

While we were observing the site and carrying out our

respective tasks, the guard also lamented about the poor lack of maintenance of

this site. There are very few guards in the day; by night there are just two.

As a result, the site has been encroached upon by thieves and drunkards, thus

making it unsafe for people to explore the site alone without supervision. The

government offers them very less salary and even the workers, which according

to the guard can turn the site into a beautiful garden, do not have the will to

do this. When asked about the lack of signages inside the fort complex, he told

us that ASI had, in fact, installed a lot of information boards, but all of

these were ripped off or broken by the people. On the signboards that do

survive, one can see remnants of black paint splashed over them.

The heavy vegetation cover is home to a lot of snakes (the

incessant slithering noises that I heard were not my delusion as the guard

really confirmed their existence) and insects that roam around the whole fort

complex. The paths are not clear and covered with thorn bushes, thus making it

difficult to explore the site in its entirety. There was waste littered around

as well by the visitors and no dustbins were in sight. By this time, all three

of us knew what exactly “Protected Monument” meant.

|

| Fig 5: The Queens Quarters |

We encountered another corridor that might have housed

rooms, a ruined structure which was probably the court, the Bijay Mandal and

the Delhi and Elephant gates. There was also a madrasa in sight alongside the

Queen’s Quarters. Further on, we saw the first underground passage in the form

of the Meena Bazaar. While we were eager to go inside the passage, the heavy

stench and the existence of multitude of bats discouraged us to do so. The

guard told us that only one underground passage survives in a good condition.

Another baoli was also visible in this vicinity, its condition, however, not

that good, and it was covered with barbed wires all around. And finally we analyzed

the fortification walls and the bastions, the long line of fortification

exuding the site’s power still. It is from here that the city of Adilabad is

visible, a site in much worse shape than Tughlaqabad.

|

| Fig 6: A bastion part of the fortification wall. Adilabad can be seen further ahead. |

For our second leg of the site cover, we went to Ghiyath

al-Din’s Tomb. It is during this time that

|

| Fig 7: Tomb of Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq |

sun blazed intensely and monkeys

rustled in the trees that we passed by. A stunning piece of architecture,

exquisite in red sandstone and marble, this tomb was constructed around 1325

CE. The tomb has a fortified outer structure with turrets at each corner. The

inner structure has the main mausoleum, which is surrounded by arched colonnades

running on all four sides, each of the three sides having a small pavilion

like structure built in them. A very interesting feature is that the walls of

the mausoleum are not built upright but rather have a tilt to them, i.e, the

base is slightly wider than the top. Going into one of the pavilions, we

discovered a small chamber filled with carved pillars and some jali windows. A

path further led us to an open pavilion. The tomb of Zafar Khan is also present

here which is the oldest structure that exists on this site.

|

| Fig 8: Members Diptarka and Debyani measuring one of the arches. |

Our experience here was in complete contrast with the one we

had in the Tughlaqabad fort. There were proper signboards and the site was

really clean. One could also see certain indigenous influences on the structure

as well. This hinted at the increasing amalgamation between two distinct

cultures in the subcontinent. Our experience of covering the whole site really

made us reflect on what more could have and could be done to preserve, conserve

and protect such an important site.

|

| Fig 9: An arched colonnade in the Tomb complex. |

For starters, connecting with organizations such as INTACH

in order to improve the condition of the fort will really go a long way. Also

the government as well as the ASI should increase the number of staff employed

at this site and ensure greater incentives to them so that they feel motivated

to work towards the site. Increased inspections of the site and regular

installation signboards would also be helpful. However, a major chunk of

responsibility falls on us citizens too. Spreading adequate awareness about the

site and its condition is the first step. We should understand that we have a

moral duty towards monuments too and thus subjecting them to any kind of damage

is unacceptable.

The walls and structures of the Tughlaqabad carry

inexplicable stories in them, a rather interesting and mysterious narrative in

them. Thus, the site cover of this site really fueled the fire in us three to

see that this site is literally not lost forever.

SOME MORE PHOTOS FROM THE SITE:

|

| Fig 10: A hammam bath in the fort complex. |

|

| Fig 11: Ruins of a Madrasa near the elephant gate. |

|

Fig 12: A room assumed to be have been used as a Maze.

|

|

Fig 13: Ruins of the court.

|

|

Fig 14: The underground Meena Bazaar.

|

|

Fig 15: A pavilion in the Tomb of Ghiyath al- Din

|

|

Fig 16: A pillared chamber inside one of the Pavilions in the Tomb complex.

|

|

| Fig 17: Inside an arched colonnade in the tomb complex. There is also an unmarked grave at the end. |

Very nice blog, thank you for sharing. If anyone want a best villa in Delhi NCR for sale , then you visit Riveirahills.

ReplyDeleteThis was such a lovely read, really enjoyed this post! Keep sharing such amazing information! Also, do check out my profile Indian Tiger Safari, when you get a chance.

ReplyDeleteThis is such an informative and well-written post about Tughlaqabad Fort! I appreciate the historical insights and architectural details you've shared—it really brings the site to life. I'm planning to visit in the future and your blog has made me even more excited. Also, do check out my profile: destinique.com. Keep sharing such amazing content!

ReplyDelete